At first glance sumo is nothing if not bizarre: overweight men dressed in an enormous thong pushing each other inside a small ring where the pre-ceremony is usually longer than the actual fight. However, delve a little deeper and you will find a unique and technical sport with a rich history and wrestlers whose rigorous training regime and dedication cannot fail to impress.

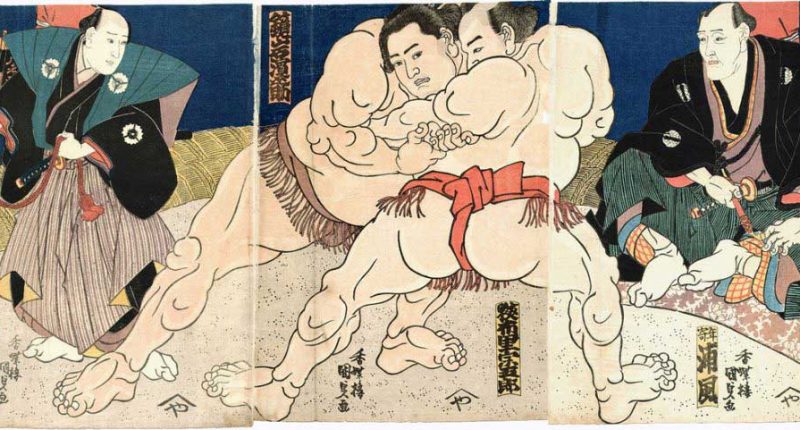

Sumo is said to have its roots in a Shinto ritual dance where the most powerful men displayed their strength in front of the kami (gods or spirits) as a sign of respect and gratitude to bring in a good harvest. Later it was used as a way to compare strength and determine those fighters most adept in hand-to-hand combat. It wasn’t until the Edo period that professional sumo wrestlers emerged from the ranks of amateurs and regular competitions began to take place. The best fighters began to gain a celebrity-like status and sumo’s popularity quickly spread amongst the masses—the true beginning of the sport as it is known today.

The sumo wrestlers are known as rikishi in Japanese (the two characters of the kanji meaning “strength” and “warrior”). There are around 650 rikishi in the six divisions of sumo:

- maku-uchi

- juryo

- makushita

- sandame

- jonidan

- jonokuchi

The maku-uchi (the 42 best rikishi) naturally receive the most media attention. At the top of this pile sits the yokozuna, the grand champion. This position is typically achieved by winning two honbasho (major tournaments that determine rankings) in a row. There are six honbasho annually, one on each odd month of the year, and they last for 15 days. As of 2015, there have only been 71 yokozuna in the history of the sport, which should give you an idea of the difficulty of achieving this rank. Rikishi from the top two divisions (known collectively as sekitori) will wrestle every day of the major tournaments.

Sumo must be unique in that the pre-match ceremony and pageantry can be just as fascinating as the bout itself. The day before each major tournament the dohyo—the 4.55 metre diameter clay platform housing the ring in which the bout takes place—is “cleansed” to pray for the safety of the rikishi. This involves placing salt, cleansed rice, dried chestnut, dried kelp, dried cuttlefish, and nutmeg berry in a small hole made in the middle of the ring as offerings to the gods.

The rikishi step onto the dohyō from the east and west, the east side rikishi entering first. They enter the ring and perform a ritual called shiko—the leg raising and stomping that is probably the act most commonly associated with the sport outside of Japan. This is more than just warming-up: the clapping of hands is to attract the attention of the gods, the raising of arms to the sky is to show they carry no weapons, and the famous legs raising and stomping to crush any lingering evil spirits.

With the shiko finished the rikishi leave the circle and cleanse themselves. The first ritual is called chikara-mizu (literally “strength water”), each rikishi receiving this water from the opponent they defeated last. Like the cleansing process at the shrines and temples, each rikishi will take a handful of water and swill it in their mouth. Next they take a handful of kiyome-no-shio (cleansing salt) and throw it over the ring before entering.

Once the referee (gyōji) gives the signal for the bout to begin each rikishi crouches behind a white line called the shikirisen on their half of the ring. The fight begins when both rikishi have clenched fists resting on or behind their shikirisen.

Because it is the rikishi that ultimately decide the start of the bout the moments before can be incredibly tense. The rikishi often crouch for a few seconds, cautiously waiting to see what their opponent does, before standing again to recompose themselves. They may exit the ring to their respective corners, but if they do so they must once again cleanse the ring with salt before re-entering. One bout decides the victor (this is not a best-of system) and as the first few seconds during which the rikishi collide often decides the winner you can begin to appreciate why the pre-bout deliberations are often the most intense moments of the fight.

Officially there are 82 techniques called kimari-te (“deciding hand”) by which a rikishi can win the match (e.g. push-out, neck throw, etc.). Once a winner emerges both rikishi stand at either side of the ring and bow to each other (neither should show emotion here), before the defeated rikishi leaves the ring and the gyōji officially declares the winner.

Each day of the competition starts with the lower ranking bouts before moving onto the juryo and maku-uchi matches. Each round of bouts is preceded by a special procession called dohyō-iri where the rikishi stand outside the circle of the dohyō wearing their mawashi (silk loincloth) and perform a sort of alternative version of the shiko ritual mentioned above: they clap and rub their hands to make sure the gods are watching and to symbolize the cleansing process, before leaving the ring with a flick of their mawashi to show that they hide no weapons.

Yokozuna get their own ring-entering ritual, a more elaborate and prolonged version of the shiko, performed with a gyōji and two other rikishi present on the dohyō.

The Rules

The basic rule is simple: if any part of your body other than your feet touches the ground or you step outside the straw ring the match is over and your opponent is declared the winner. During the bout the following acts are prohibited:

- Hair pulling

- Eye gouging

- Hitting with closed fists (slapping is permissible)

- Choking (although thrusting with open palms at your opponent’s throat is allowed)

- Grabbing the crotch area of your opponent’s mawashi

There are no weight classes. It’s not just about size: agility can be equally important and the smaller rikishi have the advantage that they can step aside and slip in behind their larger opponent and use his considerable momentum against him.

While historically a very Japanese dominated sports, in recent times foreigners are a common site on the sumo circuit in Japan. In fact, the rikishi who can lay claim to the most major tournament wins is a Mongolian wrestler called Hakuho Sho. Foreigners (of which a good portion are Mongolian) make up about 5% of the total number of rikishi on the circuit today.

How Can I Watch the Sumo?

See here for details on how to buy sumo tickets.

Some Sumo Facts

- Longest match? 32 minutes with two mizu-iri (short breaks when action has reached a impasse)

- Most consecutive victories? 69 wins held by Futabayama Sadaji (1912–1968).

- Heaviest sumo wrestler in history? Orora Satoshi a Russian wrestler from the Republic of Buryatia (a region above Mongolia), who weighed 271 kilograms.

- How much do they earn? Base salary is decided by rank. Yokozuna make about ¥2.8 million per month with juryo division wrestlers earning about ¥1 million per month.

- What do they eat? It’s hard to write about sumo without mentioning the staple food of their diet, chanko-nabe: a protein-rich Japanese stew consisting of fish, meat and vegetables in a chicken broth designed specifically to help the rikishi gain weight. You don’t have to be a sumo wrestler to eat chanko-nabe—there are restaurants that specialise in this type of stew.