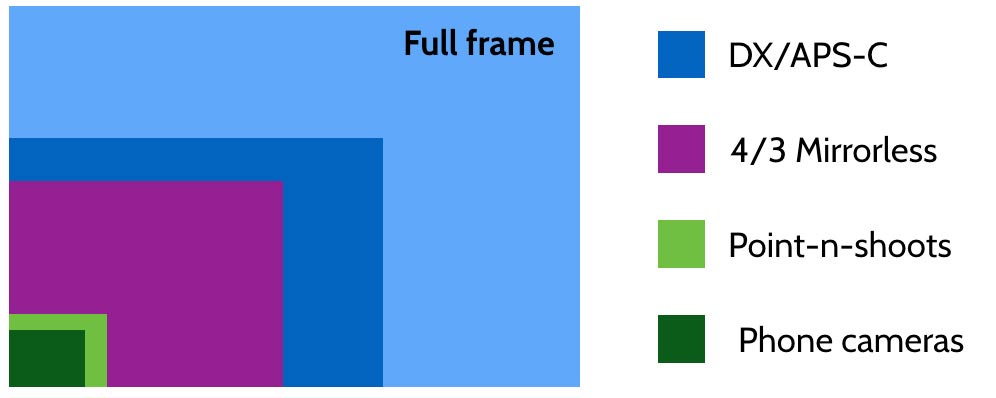

With 35mm film cameras, the “sensor” size was the size of the film negative itself—36 x 24mm (incidentally, the 35mm is the width of the film strip which gives a negative frame height of 24mm, the perforations sitting either side down the film). In today’s digital market, only semi-professional and professional cameras would have a sensor this size—the sensors on the vast majority of DSLRs available today are much smaller, whilst those on a smartphone are typically minuscule in comparison.

Here are a selection of sensor sizes stacked up on top of each other to give an relative comparison (all in ratio but not 1:1 scale).

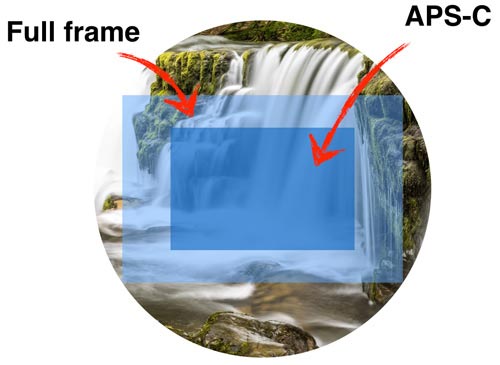

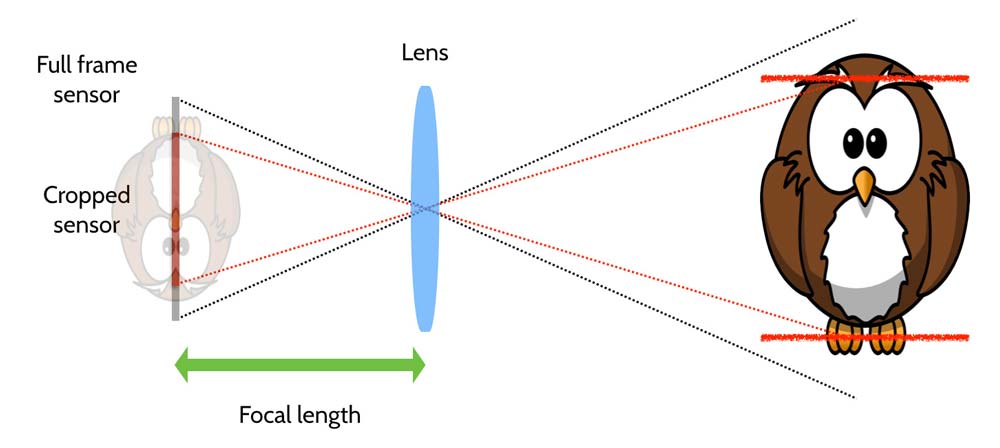

These varying sensor sizes relative to a full frame can also be expressed as a crop factor. This is simply the ratio of the diagonal of the sensor to the diagonal of a full frame sensor (~43.3mm). For instance, the diagonal of the DX sensor is approximately 28.3mm. So we have 43.3 / 28.3 = 1.53 ~ 1.5x. In practice, this means that a 50mm lens for a full frame camera will have a focal length of roughly 80mm.

This does have it’s advantages. Firstly, long focal length lenses cost a lot. A Canon 500mm f/4 lens can go for over £8,000! It’s 300mm cousin retails for around the £1,000, but on a 1.6x APS-C sensor camera this £1,000 lens now has a focal length of 1.6 x 300mm = 480mm! This is why many nature photographers (e.g. bird photographers) will opt for a smaller sensor DSLR over a full-frame.

There are two sides to the coin, however. If you’re buying a 16-35mm wide angle lens for nature photography you won’t be pleased when you realise that this is in fact a 26-56mm on your DX camera. Depth of focus is also increased with a smaller format sensor, so it’s not quite so easy to get those blurry backgrounds.

In case you’re wondering, whilst you can use a standard lens on DX (or APS-C) cameras you cannot use a DX lens on full-frame cameras otherwise you’ll get vignetting.