In some respects, the Japanese health and social support system can be a little confusing when it comes to pregnancy. This is the case for Japanese and foreigners alike. From discount vouchers and booking hospital beds to the different types of medical facilities, the system of care and support can all seem somewhat arcane.

The below is designed to give an overview of what to expect, what you need to do, as well as hopefully provide a rough idea of overall expected costs. As a disclaimer, my authority on the subject extends no further than that granted to me by the many, many phone calls to hospitals, enquiries at government offices, and hours of searching Japanese websites and hospital homepages once my wife became pregnant and the panic set in of realizing that I had no clue whom I was supposed to call or where I was supposed to go… Nevertheless, I hope it will provide some basis to get you off on the right footing should you find yourself in a similar situation.

Pregnancy & the Japanese Health System

Pregnancy is not covered under general health insurance in Japan. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, because being pregnant is not considered an illness or injury to oneself—the typical remit of health insurance. Secondly, because each pregnancy requires a different level of care there cannot be a fixed fee. Further, hospitals and clinics in Japan offer different levels of “service”, from the hotel-like treatment with your own separate room at the private hospitals to a more standard level of care elsewhere.

To provide financial support to families, Japan offers “maternity vouchers” (妊産婦健康診査費用補助券, ninsanpu-hoken-hiyō-hojoken) to expecting mothers. These maternity vouchers are essentially discount vouchers which can be used at the hospitals and clinics to reduce the cost of the regular check-ups during pregnancy. The discounts offered by the maternity vouchers differ depending on where you live (although in the 23 wards of central Tokyo they are the same), as do the non-medical auxiliary services such as free massages and house cleans post-birth.

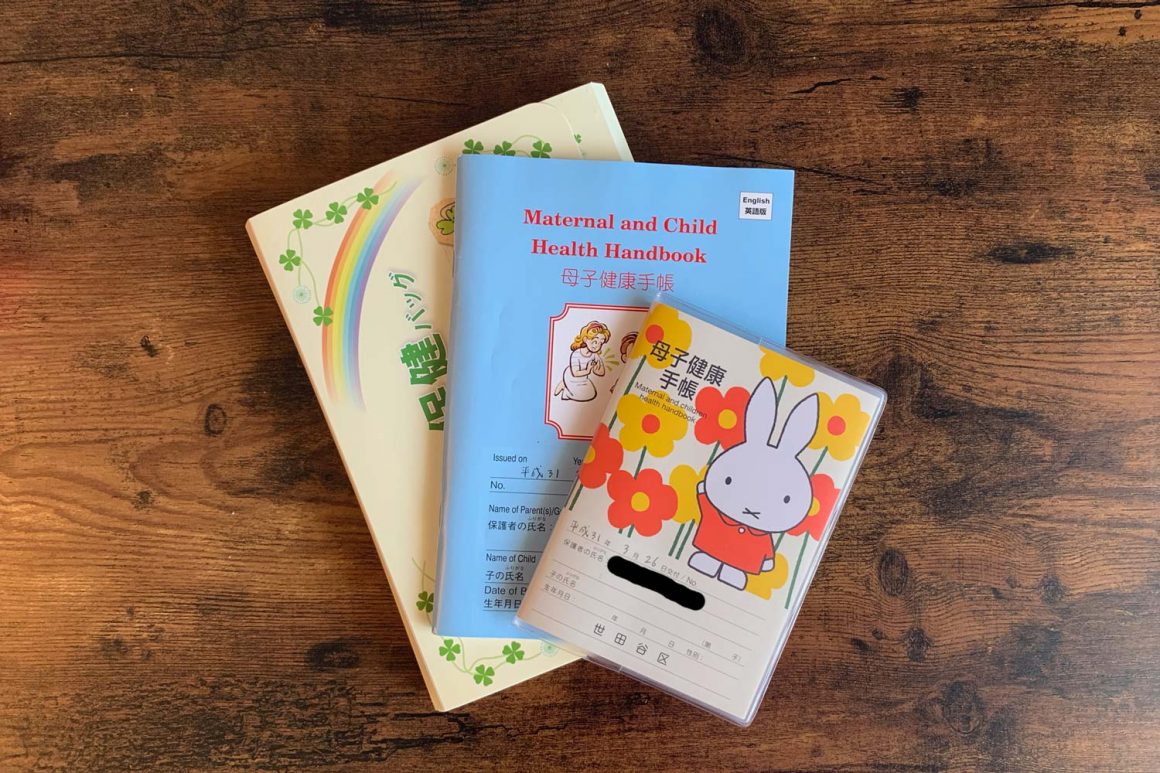

These maternity vouchers are included as part of a maternity pack expecting mothers will receive from the local city office which also includes the Maternity and Children Health Handbook (母子健康手帳, boshi-kenkō-techō). This little book is very important and will need to be taken to all checkups and hospital visits. English versions of the Maternity and Children Health Handbook are also available.

Check-ups

If the home test from the pharmacy is positive, then you’ll want to have a doctor confirm the result. This will cost about ¥5,000-10,000, and include a urine test and an ultrasound (depending on the number of weeks). Once your pregnancy is confirmed, the first thing you should do is go to your city office to collect your Maternity and Children Health Handbook, as described above. To receive this you will need to submit a “pregnancy notification form” (妊娠届出書, ninshin-todokeshutsu-sho). Do not lose this pack. In principle, the maternity vouchers cannot be re-issued.

You can now start your regular checkups. These checkups are called ninshin-kenkō-shindan (妊婦健康診断) in Japanese. You’ll need to find a clinic (more on the medical institutions below) and make your first appointment.

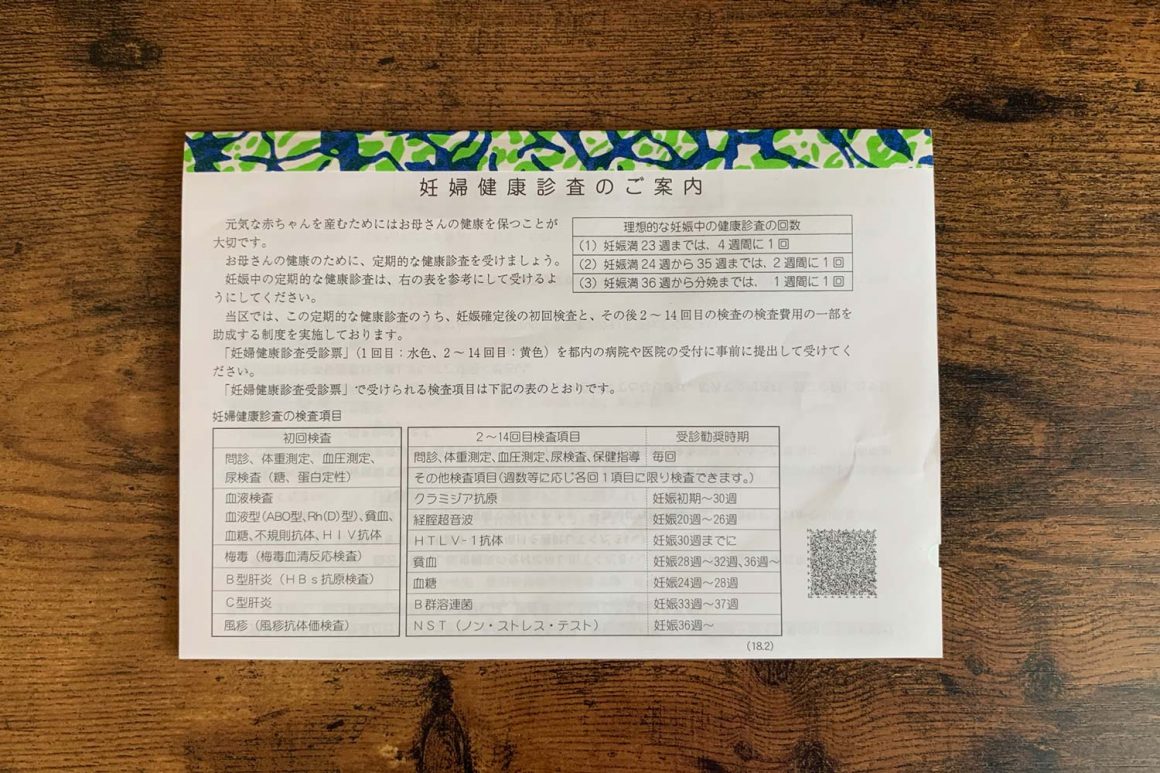

Generally speaking, expecting mothers will have 14 checkups (and will receive only 14 maternity vouchers when they collect their Maternity and Children Health Handbook). Typically, these will go:

- One checkup per month until your 23rd week

- One checkup every two weeks from the 24th until the 35th week

- Weekly checkups from the 36th week (40 weeks being the average term of pregnancy)

Naturally, the actual frequency will depend on your own situation following consultation with your doctor.

The maternity vouchers act as discount vouchers; they do not cover the full cost of the check-ups. With the vouchers, the cost of these check-ups roughly breaks down as follows but costs vary depending on the hospital or clinic, as well as the medical diagnosis.

- ¥10,000 to ¥15,000 for the first health check-up which includes multiple blood tests.

- ¥3,000 to ¥5,000 per check-up after that (if blood tests are required this will increase the cost to ¥10,000-15,000)

All told, you should expect the checkups to cost about ¥100,000 ($682) in total (after the discount vouchers). Additionally, you may have costs relating to prescriptions for symptoms during pregnancy (e.g. headaches, constipation relief, etc.), but these should be covered under your general health insurance.

Choosing a Hospital

What may surprise some is that the majority of hospitals, clinics, and maternity homes in Japan require expecting mothers to make a reservation for the birth in advance. In Japanese, this is called bunben-yoyaku (分娩予約). You can begin making enquiries once you know your expected delivery date, which is usually around the 8-10 week stage of pregnancy. Reservation enquiries need to be made even in the case where you’re going for regular check-ups to the same hospital or clinic where you want to deliver (and thus the doctors and nurses are fully aware of your expected delivery date). This is because some women choose to give birth at hospitals different to their regular check-up place because, for example, they want to travel back to their hometown to give birth so that they can be closer to their parents. In any case, the more popular hospitals get booked quickly so it’s important to act fast. You will need to pay a deposit at the time of reservation. This differs by hospital but it seems that between ¥100,000 ($682) and ¥200,000 ($1,365) is common (more on costs later).

Unlike some other countries, women spend on average about six days in hospital in Japan from the time between going into labor and leaving the hospital with their newborn. Accordingly, choosing where to deliver requires a degree of research and planning. Broadly speaking, there are three types of medical institutions in which mothers can give birth.

1. General Hospitals & University Hospitals

General hospitals and university hospitals are favoured by some because they have the facilities and medical staff on hand to deal with any complications that might arise during childbirth. The demerits are that waiting times for checkups can sometimes be longer, you may not see the same doctor each time you go, and the food and general level of “service” might not be as good as at the private hospitals and clinics.

2. Private Hospitals

Not all private hospitals (個人病院, kojin-byōin) or clinics (診療所, shinryō-sho) have facilities to deliver a baby. Some will be able to provide regular checkups including ultrasounds and blood tests, but require the expecting mother to deliver at another hospital; others will specialize in something else entirely. Private hospitals and clinics are essentially the same thing (the distinction is one of size in terms of number of beds). Private hospitals and clinics that do have childbirth facilities will usually be able to offer a better level of comfort versus general hospitals. This might mean more dedicated and personalized care, better food, a private room, or the benefit that the doctor with you for the regular check-ups should also be present at the birth. Obviously, this extra level of care and service comes at a cost, and private hospitals and clinics can be considerably more expensive than general or university hospitals. However, in “higher risk” cases such as where the mother is pregnant with twins or is older, the private hospital may advise delivery at a general hospital.

3. Maternity Homes

Maternity homes (助産所, josan-sho) are clinics that specialize only in delivery. They do not accommodate regular checkups. Further, they cannot perform more complicated deliveries such as a Caesarean section. Maternity homes generally provide a more homely environment for natural births, and are typically cheaper than general and private hospitals.

To add some context to the above, roughly speaking, just over half of women in Japan choose to give birth in a private hospital; just under half in a general or university hospital; and less than 5% opt for a maternity home.

Understand the Rules & Facilities

Hospitals and clinics sometimes have certain rules and conditions by which families must abide. For example, some clinics are female only and do not allow males to accompany their partners; some will not deliver the baby if the mother has not been attending that clinic or hospital for regular checkups since early in their pregnancy. Consultation hours also differ; notably, not all places offer appointments at the weekend.

Further, what the medical institutions can and cannot offer in terms of medical services also differs. For example, not all places can offer “painless delivery” (an epidural injection during labor to relieve pain); others have more advanced ultrasound technology, and so on. Incidentally, natural births are encouraged in Japan and places offering epidurals are limited, with those that do often only making them available during normal work hours—not much help if you go into labour at midnight. Japan is also one of a handful of countries where episiotomy is still widely practiced.

Beyond that, medical institutions are chosen based on word-of-mouth, reputation, proximity to home, and so on. Many expecting mothers will visit multiple places to see the facilities, and the home pages of the private hospitals and clinics will often have photographs of comfortable hotel-like rooms or well-prepared courses dinners to entice you.

What about English speaking staff?

There are places in Tokyo that have English-speaking staff, but many of these are located in Minato Ward—unsurprising given that a disproportionate number of foreigners live here. Equally, hospitals which don’t actively promote their ability to provide services in English may nevertheless have doctors and nurses with good language skills. If your Japanese isn’t good enough to make such enquiries then you’ll need to ask a friend or find a place that is geared towards foreigners. In Tokyo, your best bet is hospitals and clinics in Minato Ward and Shibuya Ward.

Changing Hospitals

In cases where you wish to change clinics (perhaps due to a move during pregnancy) or intend to deliver at a hospital that is not where you have your regular checkups, you will need a referral letter (紹介状, shōkaijō) from your current hospital or clinic. This needs to be written by the referring doctor and will cost about ¥3,000. This referral letter, along with test results, will then be submitted to the new hospital.

Typically, you will need to have your regular check-ups at the hospital or clinic where you will deliver from about the 32nd week of your pregnancy, regardless. In other words, you cannot continue to attend a separate clinic all the way up until labor and then turn up at the other hospital just to give birth. They understandably want to examine you in person beforehand.

The Costs

As mentioned above, women spend on average six days in hospital for childbirth in Japan. 2016 statistics show that nationwide ¥505,759 ($3,451) was the average cost of a natural birth. In Tokyo, this creeps up to ¥621,814 ($4,244). These figures are averages and there are some paying considerably more. You can see the statistics by prefecture and type of institution here (Japanese only).

To support the financial burden of childbirth, families are given a “childbirth lump-sum allowance” (出産育児一時金, shussan-ikuji-ichikin). This amount is ¥420,000 ($2,866) per child. Therefore, taking the national average figure of ¥505,759 ($3,451), the amount that you would have to pay from your own pocket is this figure less the childbirth lump-sum allowance, or about ¥86,000 ($587).

It used to be the case that families would need to pay the full medical costs of childbirth directly to the medical institution where the mother gave birth, but in 2011 a direct payment system was introduced which allows the medical institution to claim the childbirth lump-sum allowance on your behalf, thus reducing the burden of an otherwise large payment.

Preparing for Delivery

There are many more qualified medical websites to talk about preparation for delivery but the below are a couple of important points for giving birth in Japan.

Hospital Bag

Like any country, expecting mothers should have hospital bag prepared as their due date approaches. But with mothers staying in hospital for about 6 days post-birth many have full suitcases prepared for the stay. This means more clothes, more personal items (e.g. phone chargers, books, magazines, etc.), as well as the following items:

- Maternity and Children Health Handbook

- Health insurance card

- Inkan / Seal (if you have one—foreigners often just sign instead)

- Patient Registration Card (診察券, shinsatsu-ken)

Register for a “Maternity Taxi”

Unless you have your own transport, you’re going to be relying on a taxi to get you to the hospital. While taxis are everywhere in Tokyo, you don’t want to be frantically running up and down the road in the middle of the night trying to hail one while your partner is back home in pain. The Japan Taxi app is okay in the Tokyo area but it’s not something I would want to rely on in an emergency. Fortunately, many taxi companies offer a maternity service (陣痛タクシー, jintsū-takushii). You register your details online and then you have access to a special hotline which jumps you to the front of the queue and is open 24 hours per day. Websites for a few of the main companies: Nihon Kotsu, Ebara Kotsu, KM Taxi. The companies charge around ¥500 on top of the metered charge for the service.

Post Birth

Registering the Birth

First, you need to register the birth at your local city office within 14 days and to do this you will need a birth certificate issued by the medical staff at the hospital where your child was born. At the local city office you should submit a Birth Notification Form (出生届, shussan-todoke). Also take your Maternity and Children Health Handbook because you will given a small certificate which you should cut out and stick in your handbook.

You should then apply for a Birth Notification Certificate of Acceptance (出生届受理証明書, shusshōtodoke-juri-shōmeisho) at the local city office which, because a Family Register is not created for foreign nationals, is often used as an official Birth Certificate. You may also need this Birth Notification Certificate of Acceptance to register the birth the embassy or consulate of your home country.

Applying for Permission to Stay

Children of foreign nationals born in Japan are granted permission to stay for 60 days without any status of residence. If your child will stay in Japan longer than 60 days and you hold a resident status other than Permanent Resident (特別永住権, tokubestu-eijūken), you need to make an Application for Certificate of Eligibility (在留資格取得許可申請, zairyū-shikaku-shutoku-kyoka-shinsei) at the Japanese Immigration within 30 days of birth. This can be done even if your child does not yet have a passport. Required documents will depend on your resident status, but typically you will need to submit the following documents.

- An application form (available at immigration)

- A questionnaire for both parents (only one needs to be present but you need to know the passport number and residence card number of your partner). The questionnaire is available at immigration.

- Residence Certificate (住民票, jūminhyō) for all members of the family including your child.

- Birth Notification Certificate of Acceptance (出生届受理証明書, shusshōtodoke-juri-shōmeisho)

- Taxation Certificate (課税証明書, kazei-shōmeisho)

- Certificate of Tax Payment (納税証明書, nōzei-shōmeisho)

- Certificate of Employment (在職証明書, zaishoku-shōmeisho)

The issuance of a residence card for your child typically takes 14 days (the card will not show your child’s photograph so you do not need to prepare one for the application). In order to collect the residence card you would ordinarily need to show your child’s passport, but this may not have been issued yet. Instead the immigration bureau will accept a certificate or receipt from your embassy showing that you have applied for one. The length of validity on your child’s residence card will depend on your status as the applicant.

Child Support

To support families with the cost of raising a child, child benefit is provided to all families. It is called jidō-teate (児童手当) in Japanese. The application for child benefit payments must be made by the “householder”, which is defined as the parent with the highest income. How much you get per child, per month depends on the income level of the householder. The minimum regardless of income is ¥5,000, and the maximums are as follows:

- Until 3 years of age: ¥15,000 per month

- From 3 until 12 years of age: ¥10,000 per month (¥15,000 from the 3rd child)

- From 12 until 15 years of age: ¥10,000 per month

- Over 15 years of age: No further payments

The income limits depend on the number of dependents and are shown on the Cabinet Office’s child benefit page, but as at the end of 2018 the income limit for the householder with a spouse and two children, for example, was ¥9.6 million. Minato City’s website is also a good source for updated information in English.

How do I apply for child benefit?

You need to submit an application for child benefit payments (認定請求書, nintei-seikyūsho) within 15 days from the day after birth. Payments are made in February, June, and October of each year to the applicants bank account. Note that no proof of income is required at the time of application, but to ensure that payments are in accordance with changing circumstances, each year in June you need to submit an “update notification” (現況届, genkyō-todoke) to the municipal offices.