Dejima (出島, “Exit Island”) is a small island in the port of Nagasaki which served as a Dutch trading post between 1641 and 1843, and was the only official place of trade between Japan and the outside world during the country’s 200-year period of isolation (sakoku). Today it is a designated Japanese national historic site.

The History of Dejima and Europe-Japan Trade

In 1543 a group of Portuguese merchants, blown off course by a storm, landed on the southern island of Tanegashima. They were the first Europeans to come into contact with the Japanese. With them they brought the matchlock gun, which they sold to the local chief (hence why Japanese matchlock gun is called a Tanegashima), and heralded the beginning of Japan’s period of nanban (“southern barbarian”) trade.

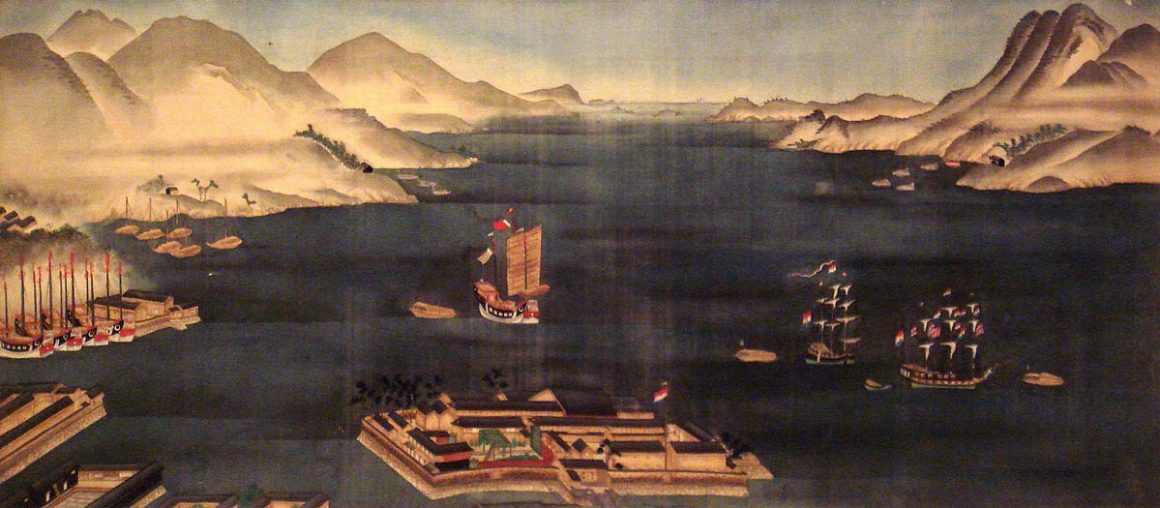

From the mid-16th century Portuguese merchant ships began arriving along the coast of Kyushu, and local feudal lords, eager to reap the benefits of trade, vied with each other to have the ships dock in their domains. The first ship in Nagasaki Prefecture landed at Hirado, but the open coasts did not provide good protection from the rough seas and so in 1570 a port was established in the bay of Nagasaki—a narrow inlet 5 kilometers from the sea.

It was not just the Portuguese, however, that had a foothold in trade relations with Japan. The Dutch had arrived in Bungo, Oita Prefecture, in 1600 and later set up a trading post at Hirado. The British also wanted a piece of the pie and were trading at Hirado by 1613. Chinese vessels were also a relatively common sight.

These developments did not go unnoticed by the shogunate, specifically the rooting of a foreign religion. Christianity had first come to Japan with the arrival of Xavier Francis in 1549, and the port at Nagasaki was a natural point from which it could flourish. Churches were constructed in the town and Japanese were being converted in increasing numbers. In 1587 Toyotomi Hideyoshi put Nagasaki under his direct rule and missionaries were banned. Later, in 1612, the Tokugawa shogunate banned Christianity altogether and burnt the churches to the ground. This period was also marked by the rounding up and execution of missionaries and the Japanese converts.

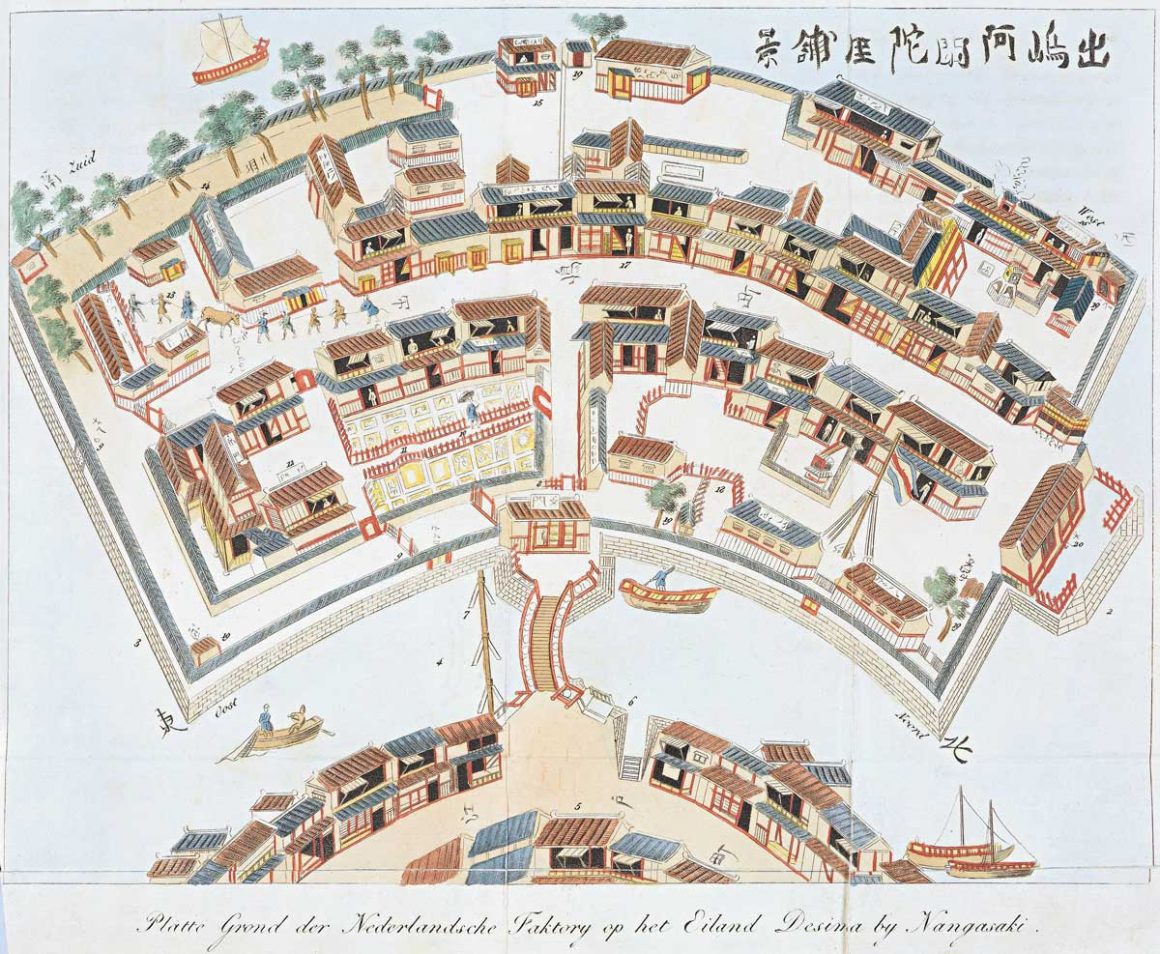

The coming and going of merchants ships was obviously a major factor in the spread of Christianity, and so while the Tokugawa shogunate initially welcomed trade with these foreign nations, they viewed the European merchants with a cautious eye. In 1634 Tokugawa Iemitsu ordered the construction of an artificial island in Nagasaki, created by cutting a canal through a small peninsula, to accommodate Portuguese merchants and limit their interaction with ordinary Japanese. This island was called Dejima.

Competition for trade among the nations was fierce. The British left as victims of this trade war, unable to compete with their better stocked rivals. The Portuguese were subsequently banned from trading as a result of their suspected involvement in a Christian rebellion against the shogunate in 1637 known as the Shimabara Uprising. The Dutch managed to stay in favour only because they had wisely provided gunpowder and cannons to the shogunate to help them crush this uprising, and for this they were granted exclusive trading rights with Japan. The terms of this arrangement, however, were such that they were forced to move from Hirado to Dejima Island. Although originally built to house the Portuguese, it was the Dutch who would claim Dejima as their trading post in Japan for the next 200 years.

Trading continued more or less freely until the shogunate decided to limited trade to two vessels per year in the late 17th century. It was facing a financial crisis and becoming increasingly aware of the impact that importing luxury goods and exporting silver and copper was having on its coffers. This development, however, also resulted in a diversification the goods exchanged, and from the early 18th century Japan began to trade more and more of its own produce. Japan’s ceramics, in particular, were highly valued in Europe and are widely understood to have influenced pottery makers back home. Likewise, the importing of sugar, medicines, and silk had a permanent and long-lasting impact on the lives of the Japanese.

But it was not only consumer goods that were exchanged. Hundreds of physicians and interpreters stayed on the small island, and a great deal of culture and scientific exchange that took place with the natives. For example, from the 18th century onwards Dutch medical texts and journals were translated and subsequently found their way into the hands of practitioners in Japan. These texts oten challenged the Japanese understanding of the anatomy, based as it was on Confucian beliefs.

With the opening up of Japan in the mid-19th century, Dejima was no longer needed as a trading post and over time Yokohama, today Japan’s second most populous city, became the country’s commerce gateway for the outside world. Landfill projects at the end of the 19th century resulted in Dejima losing its distinctive fan-shape to a sea of surrounding buildings. Dejima’s own structures subsequently fell into disrepair and in the early 19th century there was a genuine danger that Dejima’s fascinating history would be lost before reconstruction plans were outlined in the post-war period.

Life on Dejima

Dejima for those that lived on the island was akin to a small town. There were 10-20 employees of the Dutch East India Company on the island at any one time, and each had their own tasks to perform as they prepared for the next ship to enter Nagasaki’s bay.

Many Japanese also worked on the Dejima. The highest in rank was the otona (乙名) who decided who could enter and leave the island—courtesans being among those who enjoyed practically free access to come and go. Below him were clerks, cooks, bookkeepers, and a host of other workers whose job it was to keep things running and ensure that nothing was smuggled onshore.

Visiting Dejima Today

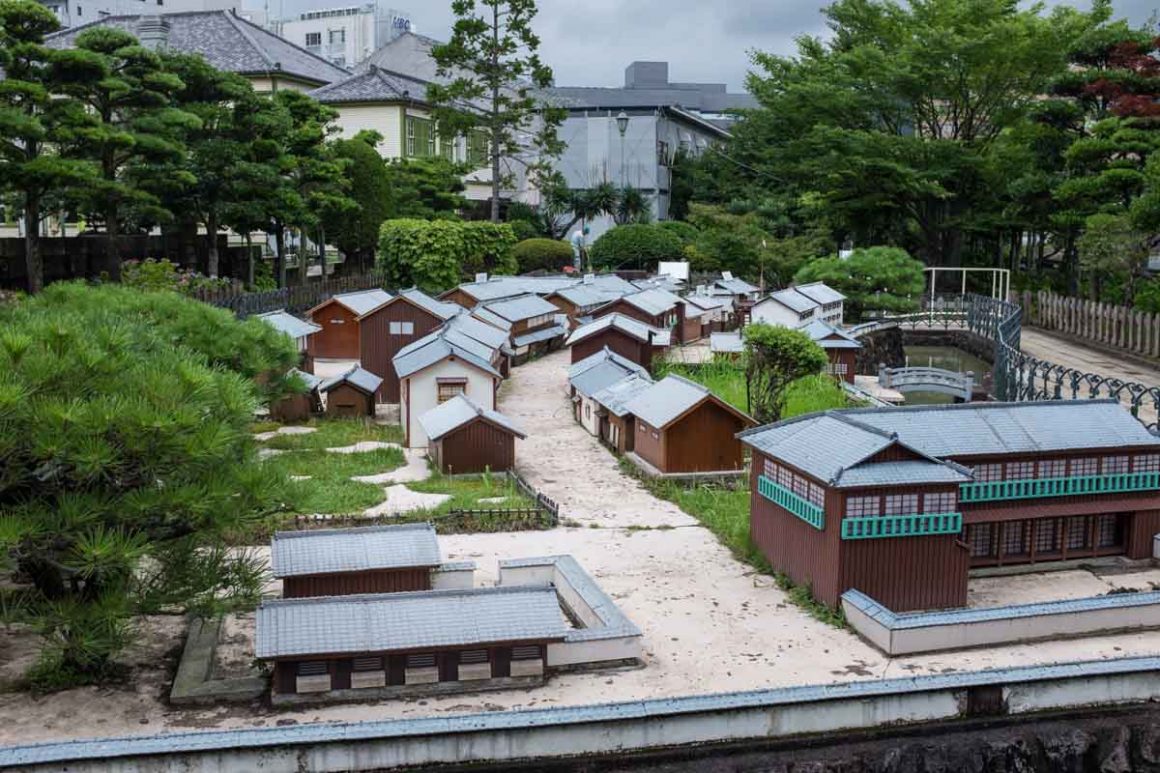

Reconstruction work began in earnest in the late 20th with the aim of re-building the island’s structures to their Edo-period state. The original foundations and walls were excavated, and rooms were reconstructed based on 19th century drawings. In February 2017, a bridge connecting the former entrance to Dejima to the Nagasaki mainland was completed and the two sides were joined for the first time in 130 years.

Much of the restoration work has been completed today, and visitors walking around the island can get a good sense of what life must have been like there during the Edo period. Rooms have been furnished with contemporary artifacts, and exhibits are well displayed with both Japanese and English explanations. The island is not very large (120 x 75 meters) with about 20 buildings in total, but it is definitely worth taking the time to view all of the rooms. Dejima is another fascinating piece of a city that, in many respects, is intertwined with Japan’s history more than any other, and an absolute must for any visit to Nagasaki.