There are three core scripts in Japanese: kanji, hiragana, and katakana. In addition, romaji is used to give Latin phonetics to the symbols of the Japanese scripts.

Romaji

Like pinyin for Chinese, romaji is used to apply Latin script to Japanese characters (ji means letter, roma refers to the romanisation). Regrettably, it’s usually the first thing you’ll be introduced to when you start learning Japanese as teachers put off introducing hiragana and start by writing simple sentences like the following in romaji.

| watashi ha gakusei desu. |

| I am a student. |

Approximate phonetics should be obvious when you see romaji, noting that the pronunciation of “r” is actually closer to “l” and the particle “ha” is actually pronounced “wa”. Elongated vowels are represented with an over line bar (e.g. ō) or a circumflex (e.g. ô), so the correct spelling of romaji is actually rômaji.

Hiragana

Hiragana is used to form the grammar. Particles and conjugations of verbs are written in hiragana and you can think of it as the main “alphabet” in the language. Technically speaking, we should refer to hiragana as a syllabary since each character represents a defined syllable, the pronunciation of which will not change regardless of order or position in the sentence. This is unlike English where the pronunciation of “s” differs between “sun” and “shine”, for example. There are 46 base syllables.

Katakana

Originally developed from parts of Chinese characters, katakana is today used to write words borrowed from other languages, e.g. cake, meeting, business, hot dog, computer, etc. In many cases these words do exist in Japanese but it is by no means uncommon for Japanese speakers to deliberately use the English word (with the Japanese pronunciation) instead. These foreign words sometimes undergo their own transitions within the Japanese language, pushed, pulled, and abbreviated until they are no longer recognisable.

| Starbucks ⇒ sutābakusu ⇒ sutaba |

| Reschedule ⇒ risukejuru ⇒ resuke |

Each syllable in hiragana has a one-to-one relationship with katakana, and vice versa. Hiragana and katakana are simply two different ways of writing the same syllable. You can think of them as like uppercase and lowercase letters in English: “APPLE” and “apple” would look like entirely different words to an alien, but for us they have exactly the same meaning and pronunciation.

Kanji

Last but not least, kanji—essentially Chinese characters. Well, originally at least. They came to Japan from China about 2,000 years ago and have since transformed such that many are now unique to the Japanese language (altered forms of the original character).

Since mainland China promoted simplified versions of Chinese characters to improve literacy in the 1950s, a kanji and simplified Chinese character that derive from the same traditional character can now be unrecognizable from each other.

| English | Choice | Invention |

| Traditional Chinese | 選擇 | 發明 |

| Simplified Chinese | 选择 | 发明 |

| Kanji | 選択 | 発明 |

You can see that not all characters have changed. Many of the more basic characters (e.g. 明) have remained the same. Other characters are different in all three scripts (e.g. 発). It’s not too far from the truth to think of kanji as a halfway house between the traditional and simplified Chinese characters in terms of difficulty.

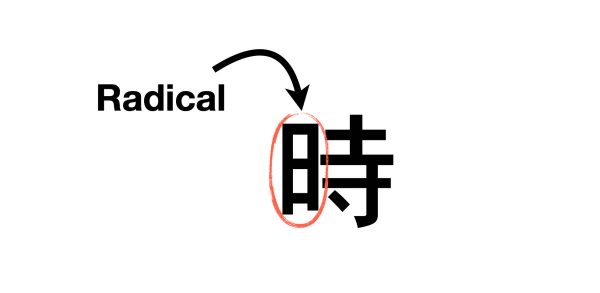

Kanji are classified by their radical (roots). These are characters (which can in some cases be kanji on their own) which appear within the character. In total there are 214 radicals, although not all are in use in modern Japanese.

Each radical has a general meaning in its own right which often gives you a sense for what the kanji in which it is used might mean.

| Kanji | English | Radical | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 時 | time | 日 | day, time |

| 詩 | poem | 言 | words, to say |

Furthermore, the radical can be used to look up an unfamiliar kanji as each kanji has only one radical. Admittedly, nowadays there are a number of online resources and apps that let you draw a character on screen, but if you are using a good old paper dictionary knowing the radical is the quickest way to find a kanji.

So how many kanji are there? Well, to attain level one in the kanken—an examination specifically designed to test kanji ability—you would need to be able to write and read around 6,000. This is a feat far from the reach of most native Japanese speakers and those that pass level one will have studied for months if not years.

To be able to read newspapers, magazines, books, and so forth you will need to know around 2,000 kanji. The list of characters in common use (jōyō-kanji) currently stands at 2,136. About 2,000 is also the number of characters that you will need to know to pass level N1 of the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), the main test for foreign learners of the Japanese language.

To be able to “get by” about 1,000 is a good estimate: 1,006 kanji is the number that Japanese school children should know by the time they graduate from primary school at around 11 years old (kyōiku-kanji).

What makes learning kanji more difficult compared to Chinese characters is that there is more than one reading for each character (in Chinese most characters will have just one pronunciation). The readings are divided up into on-yomi and kun-yomi, the former representing the readings that have come from the original Chinese character and the latter representing the native Japanese reading.

Now, in theory, you could write everything in Japanese in hiragana (or, indeed, katakana); kanji aren’t necessary for grammar. But because there are no spaces in Japanese sentences kanji help visually break up the words making it much easier to read text. They also play an important role in distinguishing between homophones (of which there are many given the comparatively limited repertoire of phonetics from which the Japanese language is formed).

In the following example the first sentence is written naturally (using both kanji and hiragana) while the second is the same sentence written using only hiragana.

| 卒業証明書の和訳が必要です。 |

| A Japanese translation of the graduation certificate is required. |

| そつぎょうしょうめいしょのわやくがひつようです。 |

| A Japanese translation of the graduation certificate is required. |

To Japanese-speakers, the latter sentence is a bit like reading the following in English.

“AJapanesetranslationofthegraduationcertificateisrequired.”

In other words, possible; but it takes longer and is likely to result in a headache.

You will see all three scripts—hiragana, katakana, and kanji—used in books, posters, advertisements and so on while in Japan.