Tokugawa Ieyasu installing himself as shogun did not wash away the grievances felt by those daimyo with ambitions for power or who thought Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s son, Hideyori, the legitimate successor. Ieyasu exacerbated such tensions by rewarding those daimyo who had sided with him at the Battle of Sekigahara (fudai daimyo) with land taken from those who had not (tozama daimyo). It was only with Ieyasu’s victory at the Siege of Osaka in 1615, which ended with Hideyori committing seppuku, that the Tokugawa clan could concentrate on government. No chances were taken: Hideyori’s 8-year-old son, Kunimatsu, was captured and beheaded in Kyoto, putting an abrupt and bloody end to the Toyotomi line.

Despite the relative stability that the removal of Ieyasu’s main rival brought about, something still needed to be done to address the fragility of rule in a newly-unified Japan. To this end the Tokugawa shogunate began to consolidate power in Edo. Construction began on the gokaido (“Five Routes”)—five highways leading out from Nihombashi which would considerably cut the time needed to travel across the country, allowing better control over the outer provinces. The third Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu (1623-51), implemented a system of sankin-kotai (“alternate attendance”) which dictated that the daimyo must hold a residence in Edo and base themselves there every other year. Moreover, during the periods when they travelled back to their home regions their wife and heir were required to remain in Edo as “hostages”. The system was primarily a strategic move to lessen the chance of rebellion, but it also had important secondary effects. Firstly, the more powerful daimyo travelled in processions over 1,000 men strong, which proved a considerable financial burden and limited their ability to build private armies. Secondly, the presence of the daimyo and their entourage in Edo helped cement the city as the de facto capital (Kyoto remained the residence of the emperor as well as the official capital until 1868).

A huge wave of public infrastructure projects in Edo also helped—most notably, the reclamation of land around the delta of the Sumida River (upon which Tsukiji Fish Market and the high-rises of Shiodome now stand) as well as the commissioning of Edo castle (on the grounds of which Tokyo Imperial Palace was later built). Often the substantial cost of these projects was borne by the daimyo, further weakening their financial clout. By the end of the 17th century Edo was one of the most populous cities in the world with over one million inhabitants (at this time London had a population of about 600,000; Paris 500,000; and New York just 5,000).

Changes were also happening beneath the surface. Societal structure during the Edo period was based on shinokosho (“four divisions”) which rigidly defined a person’s status by occupation. At the top were the samurai (shi), loyal to their daimyo and paid in stipends; next were the farmers (no), highly valued because of their necessity to society as food producers; after the farmers were the artisans (ko), because their goods were non-essential; and, finally, the merchants (sho), the lowest rung on the ladder because they, as middleman, did not produce anything.

Movement up and down this hierarchy was all but impossible. So clearly defined was the social order that if a farmer were to pass a samurai on the road custom dictated that he should crouch before him in respect. However, since Hideyoshi’s Sword Hunt in 1588, which saw the farmer’s give up arms and the samurai move to the cities, the lives of the two rarely ever crossed. It was more commonly the samurai, artisans, and merchants who found their lives intertwined in the growing urban areas, and this gave rise to other tensions as the four divisions structure creaked under the pressure of social change.

The shinokosho hierarchy did not paint an accurate picture of the distribution of wealth during the Edo period: the lower ranks of samurai often lived in borderline poverty while some of the more successful merchants, especially in Tokyo and Osaka, saw their fortunes accumulate rapidly. This rise of the merchant class (the lowest rung on the social ladder, no less) was a source of aggravation for the samurai, who were finding it difficult to reconcile their status as warriors to the administrative tasks with which they found themselves burdened during this prolonged period of peace. Attempts to justify the samurai’s marginalized role led to words like bushido (“way of the warrior”) coming into parlance, some arguing that they should be thought of as a moral beacon for the rest of society. In short, the gradual evolution of society into one where the arts, manufacturing, and commerce played an increasingly important role was incompatible with the neo-Confucian shinokosho structure.

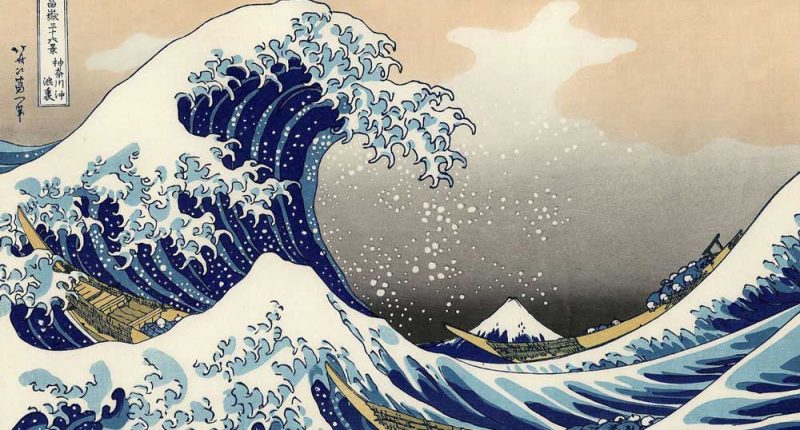

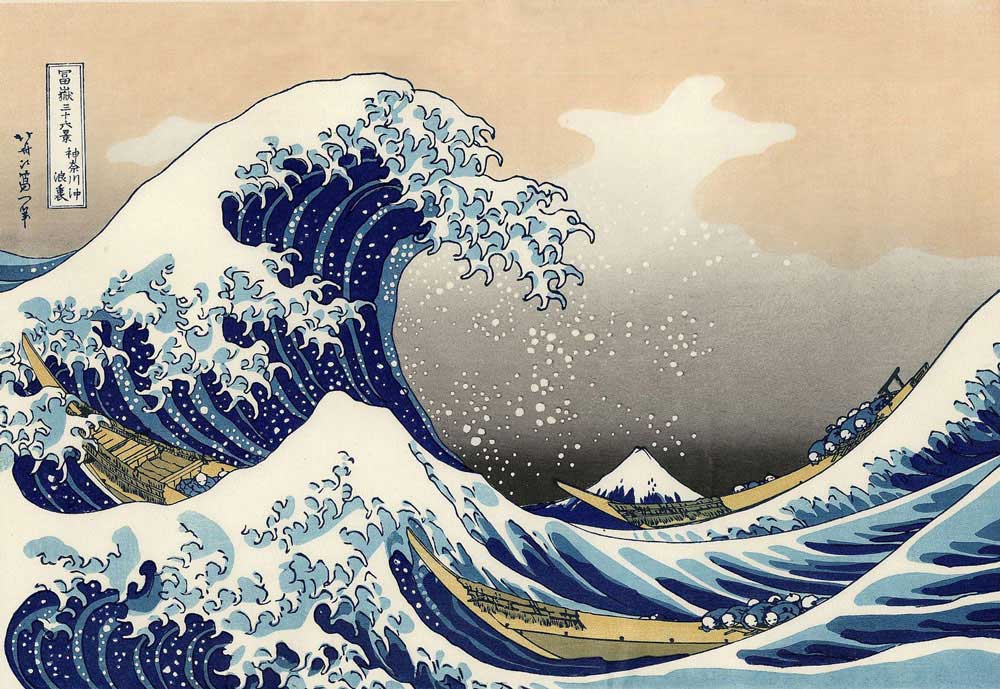

The stability of the Edo period relative to the tumultuous years of civil war also provided a base from which culture could flourish. This evolution was uniquely Japanese, and the urban hedonism and the pursuit of art and theatre that developed are forever captured in the ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”) woodblock prints that developed during this time.

But while the country changed from within, interactions with the outside world were roundly rejected. The Edo period is famous for sakoku (“locked country”), an isolationist policy which lasted for approximately 250 years.

Japan’s first direct encounter with the West was in 1543 when a Portuguese ship landed on the southern island of Tanegashima (which lies about 30 kilometers from the southern tip of Kyushu) and introduced the matchlock firearm mechanism to the country (hence why Japanese the arquebus is called a tanegashima). Six years later St. Francis Xavier, a Portuguese missionary, arrived in Kagoshima (on the southern tip of Kyushu) on a Chinese junk to spread the word of Christianity.

Despite a brief flirtation with Japan’s new visitors, by the mid-17th century the Tokugawa shogunate had decided to cut itself off from the external world: Portuguese and later Dutch traders were relegated to an artificial island called Dejima in the bay of Nagasaki, and the daimyo were given orders to fire at any foreign vessel on sight. A small amount of Western literature through trading with the Dutch in Nagasaki did manage to find its way into the hands of the scholarly elite and these manuscripts often challenged Japanese traditional thought, based as it was on Confucian values and understandings. One often cited example is the dissection of the cadaver of an old woman in the late 18th century. During the grim task medical practitioners were aghast to find that the anatomy of the human body was drastically different to that laid out in Confucian medical texts of the time, while the Dutch text they held in their possession gave a far more accurate representation of what they saw before their eyes.

It is Japan’s limited interaction with the outside world that gave it its name in English. In Japanese, Japan is nihon or nippon, a word created by two kanji which mean “sun” and “origin”, respectively. It is from this which we get “Land of the Rising Sun”. We owe “Japan” to Portuguese traders who, through the seafaring merchant networks, heard of a country called “Jepang” in Malay—itself an adulteration of zeppen (the Wu Chinese pronunciation of the two kanji of nihon). Jepang became Japan in English (it was first seen in English as Giapan in 1565), Japon in French, Giappone in Italian, and so on. Unfortunately, no concrete evidence exists as to how the country that was once known as Wa became nihon or nippon.

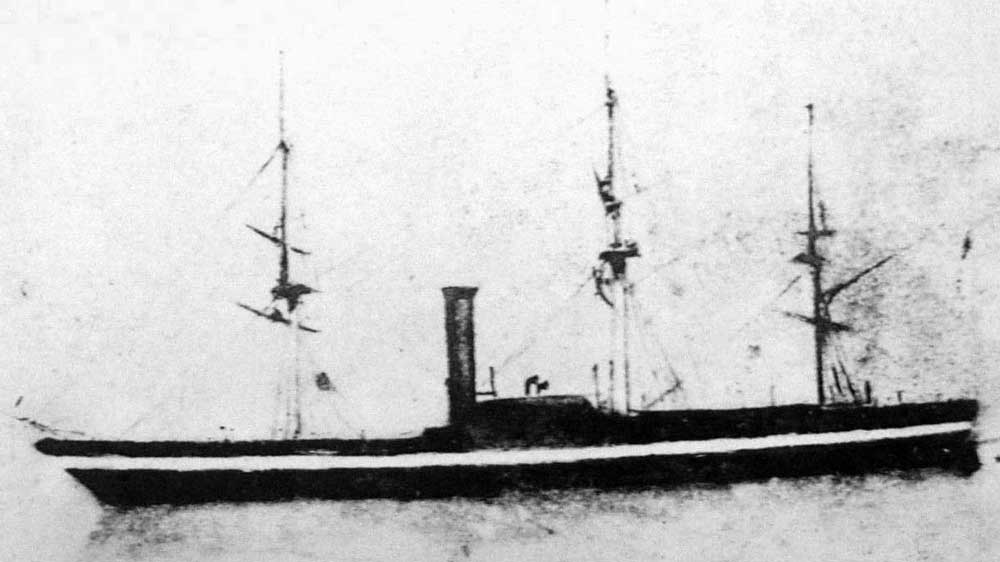

But a trickle of Western literature aside, Japan was more or less disconnected from the influences of global developments—a second Galápagos Island on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. All this changed when Commodore Matthew Perry sailed his “black ships” into Edo Bay in 1853.

Perry’s coal-fired vessels set off a chain of events in a politically fragile Japan that would—fifteen years later—result in the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and the return of control back to the emperor. Pressure against the regime came from the south—specifically, the clans of Satsuma and Choshu, united in their efforts by young revolutionaries such as Sakamoto Ryoma. These clans, dissatisfied by a fractured and ineffectual shogunate, rallied under the simple battle cry of sonno-joi (“Expel the barbarians, revere the emperor”); however, under the influence of certain intellectuals within a group of samurai known as the shishi (“men of high purpose”), they came to embrace a pragmatism that saw the need for Japan to modernize lest it suffer a similar fate to that of China at the hands of the British during the Opium Wars. For its part, the U.S. wanted open trade and an end to the execution of whalers whose ships occasionally washed up on Japanese shores.

The Harris Treaty of 1858 between the U.S. and Japan forced the country to open several of its ports to foreign trade. Japan subsequently signed treaties on similar terms with Russia, France, Great Britain, and the Netherlands. But the Harris Treaty didn’t just forcibly end 250 years of isolationism—it also sowed the seed of resentment in the Japanese, who realized that they were not seen as equals in the eyes of the Western powers. This would go on to have significant ramifications as Japan set off on a course of industrialization.

Despite almost 700 years of samurai rule the transfer of control back to the emperor was a surprisingly subdued affair. In the end, it was the tozama daimyo—specifically the alliance between the southern clans of Satsuma and Choshu—who, having seen their power wane and lands redistributed following the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, finally brought an end to Tokugawa rule during the brief Boshin War (1868-1869) and installed the emperor back as the ruling authority, an event known as the Meiji Restoration.

- Next: The Meiji Restoration & Imperial Japan

- Previous: Samurai Rule & Civil War